VISUALIZING RADIOACTIVITY

REPRESENTATIONS OF CHERNOBYL’S LANDSCAPES

Spring 2020

Harvard University Graduate School of Arts and Sciences

Advised by Peter Galison

Harvard University Graduate School of Arts and Sciences

Advised by Peter Galison

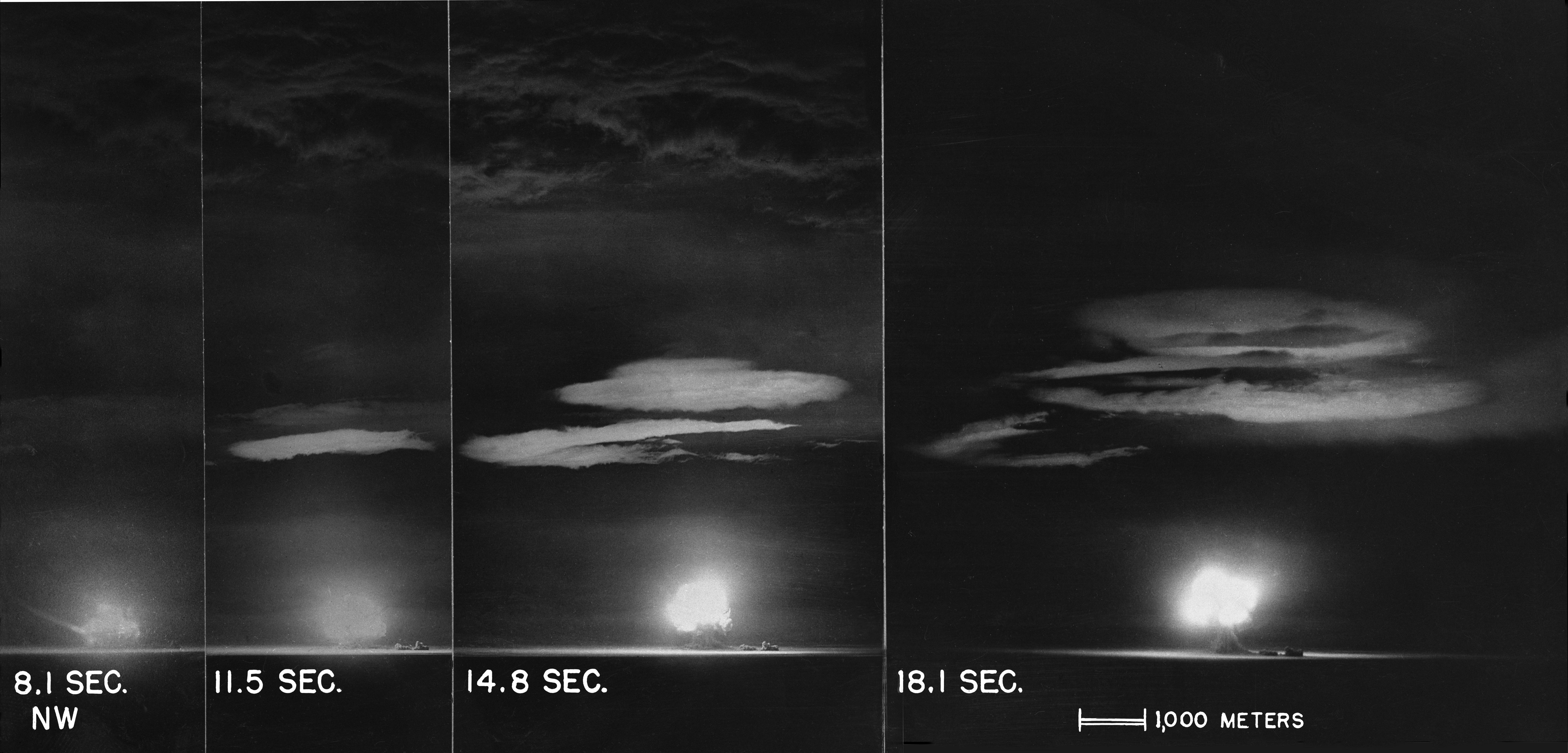

It is recognized amongst the scientific community that we are transitioning towards the Anthropocene, a recently proposed geologic epoch that describes a state of the Earth marked by an increasing human agency. The observed stratigraphic, geological, chemical and ecological shifts of anthropogenic origins suggest that humans have reached the point where their scientific knowledge and agency suffices to irreversibly alter the face and fate of the planet. Such a premise can be particularly validated from a nuclear perspective and from the initial tests of atomic bombs that marked the human as a planetary agent. We’ve undoubtedly surpassed this threshold in 1945 with the Trinity test, the first detonation of a nuclear device conducted by the US Army, which released 21 kilotons of TNT and reached a height of 200m from the first 16 ms1. The photographs that captured the first seconds of the explosion show massive scales of spatial and temporal dimensions, with radical speeds of expansion and extensive light emanating from its center. The sublime presence of the nuclear bomb became significant proof that the planet’s fate is not only dependent on “objective” naturally occurring phenomena, but also on the “subjective” human desires.

Throughout the years, these “subjective” human desires were proved not only unpredictable but also false assumptions, decisions, mistakes. The same nuclear energy that initially provoked feelings of excitement for humanity’s achievements later proved to be beyond humanity’s control, particularly in the emergence of accidental radioactive landscapes. Incidents of explosions in nuclear energy plants such as the famous case of Chernobyl in former USSR in 1986 showcased that, although we’ve been educated to use nuclear power for energy, we do not yet fully know 2 its behavior and cannot fully control its consequences in the case of an accident. In Chernobyl, radionuclides quickly invaded the landscape, marking the soil, water and air as radioactive territories and immediately rendering them as uninhabitable and life-threatening sections of the Earth. The territory’s condition cannot be reversed by any human action and can only now be compared to geologic scales of time. Using the words of a local scientist, as quoted by the photographer Gerd Ludwig, we might as well post signs in the Zone that would read as “not intended for human habitation for 24,000 years”, which is the duration of the half-life of the plutonium 239.2

A series of photographs capturing the first seconds of the Trinity, the first detonation of a nuclear device, at Alamogordo, New Mexico in 1945. Retrieved by Los Alamos National Laboratory archives.

In discussing our incapability to deal with the radical spatiotemporal dimensions of these repercussions, in the 1950s, Martin Heidegger introduced the term “enframing” to discuss the essence of modern technology. Referring to the limitations of our scientific knowledge with regards to natural phenomena, he discussed that we-humans are eventually challenged by nature more than nature can be challenged by us, and proposed that in these circumstances, it is the art that can function as the “saving power” in this problematic relationship.3 It is true that in the case of radioactive landscapes, we not only lack the knowledge and ability to revert the ramifications of our acts on the planet, but we also lack the more preliminary ability to perceive, visualize and interpret the repercussions of our acts. Similarly to the Anthropocene, the accidental radioactive landscapes are far beyond our spectrum of perception, presenting moments of invisibilities and blurriness that exceed our capacities to visualize and comprehend them. The invisibility of events such as the Chernobyl accident is not only crucial in ensuring human safety, it is problematic in allowing us to comprehend its dimensions.

Nuclear accidents pose not only issues of radical environmental devastation, but also visual representation.4 Chernobyl is an extensively studied radioactive landscape since its birth in 1986 and it can only make us wonder what have been the various attempts and methods developed to visualize the invisible radioactive forces. Let’s unravel the various modes of representation and comprehension that have been developed from the scientific and artistic domains to visualize the irreversible radioactive landscapes that have changed the physiognomy of the planet. Through the knowledge of the representation of the local radioactivities of Chernobyl, which present the most extreme and radical manifestations of the Anthropocene in its peculiar spatial and temporal scale and invisibility, we can begin to speculate and develop knowledge for the visualization and comprehension of the larger framework of this new geologic epoch.

General Leslie Groves and J. Robert Oppenheimer at the Trinity test site in Alamogordo, New Mexico. Retrieved by Los Alamos National Laboratory archives.

General Leslie Groves and J. Robert Oppenheimer at the Trinity test site in Alamogordo, New Mexico. Retrieved by Los Alamos National Laboratory archives.

Nuclear power has sparked both the excitement as well as the fear and concern in the public domain. Earlier demonstrations of nuclear power are manifested through the first detonations of nuclear devices that show a majestic performance of human power in ground and air. Sparking the excitement of the human public through its sublime character in its presentation on the landscape and representation on the photographic films, the atomic bomb became a symbol of the power of countries and federations in an era of WWII and the subsequent Cold War. A preliminary excitement, though, was soon to be followed by the concerns for the devastating repercussions of the bombings. The German philosopher Günther Anders was particularly focused on thinking of the bombings and in the 1960s declared that there had been a metaphysical change in humans from the “genre of mortals”—or being fundamentally mortal—to the status of the “mortal genre”—or the fundamentally fatal—, a position that was held throughout the 1980s.5

Such a view was particularly manifested in the case of the Chernobyl Nuclear Plant disaster of 1986. The majestic visualizations of nuclear power are radically oppositional to the documentations of the explosion in the case of the Chernobyl Nuclear Plant in April 1986. Throughout the night of the 25-26th of April, the routine reactor tests led to complete failure. The excessive and uncontrolled rise of one of the reactor’s power production resulted in the severe accident and explosion that destroyed most of the Reactor Four, including its complete interior and the building’s four million pound concrete roofing.6 The fire that emerged from the explosion led to an eruption of more than two thousand degrees Celcius, melting the surrounding cement, steel and iron structures and machinery and blending it with the uranium and plutonium into highly radioactive lava that covered all the blown flours of the complex.7 The devastating environmental and human effects appeared staggering in the initial calculations and speculations. Initial estimates included thirty-one fatalities, although such numbers were challenged later on by reports such as the 1989 Moscow News estimate of the 250 or the various 1990s inclusive approximations of over

Such a view was particularly manifested in the case of the Chernobyl Nuclear Plant disaster of 1986. The majestic visualizations of nuclear power are radically oppositional to the documentations of the explosion in the case of the Chernobyl Nuclear Plant in April 1986. Throughout the night of the 25-26th of April, the routine reactor tests led to complete failure. The excessive and uncontrolled rise of one of the reactor’s power production resulted in the severe accident and explosion that destroyed most of the Reactor Four, including its complete interior and the building’s four million pound concrete roofing.6 The fire that emerged from the explosion led to an eruption of more than two thousand degrees Celcius, melting the surrounding cement, steel and iron structures and machinery and blending it with the uranium and plutonium into highly radioactive lava that covered all the blown flours of the complex.7 The devastating environmental and human effects appeared staggering in the initial calculations and speculations. Initial estimates included thirty-one fatalities, although such numbers were challenged later on by reports such as the 1989 Moscow News estimate of the 250 or the various 1990s inclusive approximations of over

300

victims. The morning of April 26th saw radical destruction of physical structures as well as increasing mobility of human bodies that were instructed to evacuate in the periphery of the 30km from the accident. From the first few days, there was a relocation of up to 135,000 people, with the 50,000 of them originating from the cities of Chernobyl and Pripyat.8 The radical movement of people in the interior of the territory was accompanied by a series of maps that included calculations of distances between habitable areas and nuclear fallout, as well as preliminary radiation measurements that would define low and high-risk zones. Eventually, these parameters drawn on the maps would establish the first evacuation plans for the neighboring city of Pripyat and the surrounding villages, as well as the subsequent legally imposed Nuclear Exclusion Zone, as a permanent delineation of hazardous territory on the landscape.

Contrary to the radical interior movement and delineation of the landscape in the USSR, Chernobyl’s radioactivity did not initially present itself in the western world. The neighboring countries outside USSR were not informed by the state’s official documents and announcements, but instead by radioactive measurements taken 1,100 kilometers away from the explosion at the Forsmark Nuclear Power Plant in Sweden. There, in the morning of April 28th 1986, the radiation appeared in a routine radiation dose monitoring in the technician’s shoes and surprised all the workers as it seemed to be originating from contamination outside of the plant.9 Worried about the possibility of a radiation leak in the Swedish nuclear plant, the local technicians conducted further examinations of the surrounding ground, identifying particles on the grass that could be connected to the Soviet nuclear power plants. After further considerations of weather and wind patterns that occurred throughout that weekend, they verified their initial conclusion that the radioactive fallout originated from the USSR grounds. Two days after the explosion, their suspicions were ultimately verified, as the Soviet Union formally declares that there has been a nuclear accident.10

Contrary to the radical interior movement and delineation of the landscape in the USSR, Chernobyl’s radioactivity did not initially present itself in the western world. The neighboring countries outside USSR were not informed by the state’s official documents and announcements, but instead by radioactive measurements taken 1,100 kilometers away from the explosion at the Forsmark Nuclear Power Plant in Sweden. There, in the morning of April 28th 1986, the radiation appeared in a routine radiation dose monitoring in the technician’s shoes and surprised all the workers as it seemed to be originating from contamination outside of the plant.9 Worried about the possibility of a radiation leak in the Swedish nuclear plant, the local technicians conducted further examinations of the surrounding ground, identifying particles on the grass that could be connected to the Soviet nuclear power plants. After further considerations of weather and wind patterns that occurred throughout that weekend, they verified their initial conclusion that the radioactive fallout originated from the USSR grounds. Two days after the explosion, their suspicions were ultimately verified, as the Soviet Union formally declares that there has been a nuclear accident.10

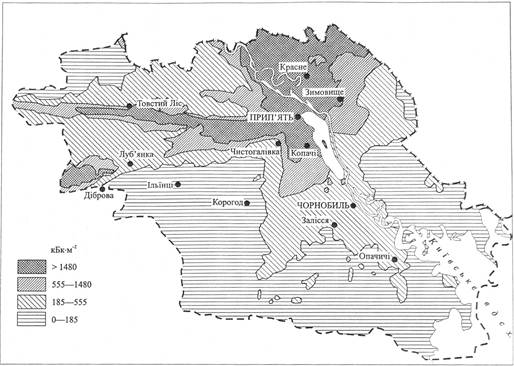

Maps showing the dispersal of radiation on April 29th (left) and May 3rd, 1986 (right). Produced by UKAEKA, retrieved from book “Environmental management in the Soviet Union”.

Contrary to the radical interior movement and delineation of the landscape in the USSR, Chernobyl’s radioactivity did not initially present itself in the western world. The neighboring countries outside USSR were not informed by the state’s official documents and announcements, but instead by radioactive measurements taken 1,100 kilometers away from the explosion at the Forsmark Nuclear Power Plant in Sweden. There, in the morning of April 28th 1986, the radiation appeared in a routine radiation dose monitoring in the technician’s shoes and surprised all the workers as it seemed to be originating from contamination outside of the plant.9 Worried about the

possibility of a radiation leak in the Swedish nuclear plant, the local technicians conducted further examinations of the surrounding ground, identifying particles on the grass that could be connected to the Soviet nuclear power plants. After further considerations of weather and wind patterns that occurred throughout that weekend, they verified their initial conclusion that the radioactive fallout originated from the USSR grounds. Two days after the explosion, their suspicions were ultimately verified, as the Soviet Union formally declares that there has been a nuclear accident.10

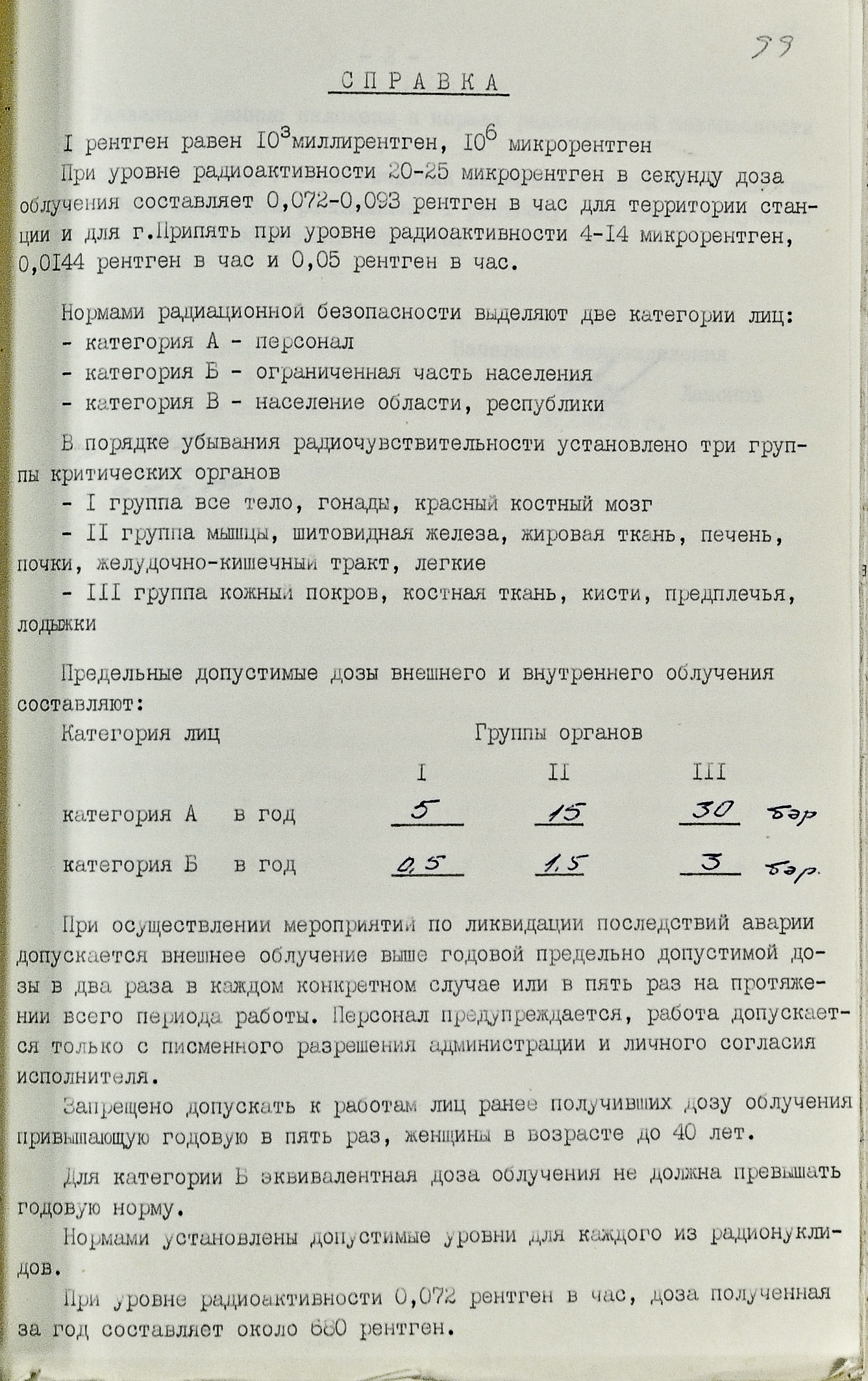

Map of the contamination of the territory of Ukraine 137 Cs as of 1987, according to Ukraine’s “Екоцентр” (Ecocenter).

Pollution map of the 137 Cs Exclusion Zone, according to Ukraine’s “Екоцентр” (Ecocenter).

Pollution map of the 90 Sr Exclusion Zone, according to Ukraine’s “Екоцентр” (Ecocenter).

The preliminary maps of the various measurements and densities of radiation in and out of USSR do not illustrate the wishful thinking of the power of a state, but rather a status of chaos. The scientific visualizations speak about a free movement of radiation clouds that, unobstructed by any authority, wander around the European grounds. Nicola Shulman remembers the words of the Chernobyl tour guide, Olena, who talks about the disobedient and anarchic character of the gamma radiation that is invisible and thus superior to any state-determined checkpoints and borders. Although invisible, it is transparent in the ways that it equally impacts all people and resembles the “emblem of Soviet lies and incompetence, and a living metaphor—with all its language of leakage, fallout and incontinence—for the welcome collapse of Soviet control.”11

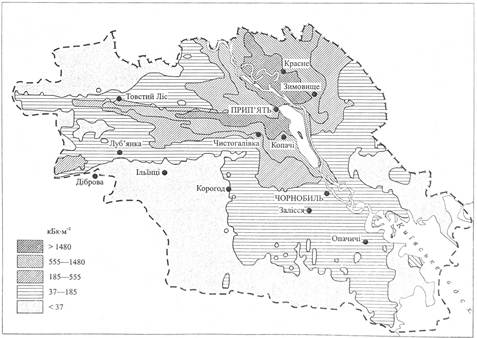

The particular political backdrop that managed the Chernobyl catastrophe played a significant role in selecting and curating the scientific observations and measurements that can be retrieved from the landscape, as well as its subsequent visual representations. For the radiation medicine that was developed by the United States and Europe, the doses were determined primarily by environmental monitoring that was oftentimes conducted remotely. The UN radiologists would use a radiation map of Chernobyl that

The particular political backdrop that managed the Chernobyl catastrophe played a significant role in selecting and curating the scientific observations and measurements that can be retrieved from the landscape, as well as its subsequent visual representations. For the radiation medicine that was developed by the United States and Europe, the doses were determined primarily by environmental monitoring that was oftentimes conducted remotely. The UN radiologists would use a radiation map of Chernobyl that

illustrates Roentgens and Sieverts in the landscape and compare the findings to earlier survivor life-span charts of the atomic bombs. The arguments on the

safety of the radiation or the dosages of the medicines were, thus, largely based on environmental data and calculations that could be conducted remotely and away from the physical location of the accident. On the contrary, Soviet doctors were denied access to any radiation measurements of the many nuclear accidents that occurred throughout the Cold War, since such data remained classified and guarded by the KGB. Without the use of radiation maps and measurements, they were trained to determine medicine doses by closely studying the affected human body and examining the nervous system, the hormonal levels and the blood cells. The observation and monitoring of the patients on-site allowed them to discern the damage at even very low doses.12

From the very first days of the accident, we see that multiple methods of observing, quantifying and visualizing radioactivity have been developed, from the radiation maps that delineate Exclusion Zones controlling people’s movement through georeferencing of collected measurements, to onsite medical examinations of the exposed-to-radiation human bodies. Throughout the years, scientists and artists have strived to form media that can represent the experience of this peculiar geography.

safety of the radiation or the dosages of the medicines were, thus, largely based on environmental data and calculations that could be conducted remotely and away from the physical location of the accident. On the contrary, Soviet doctors were denied access to any radiation measurements of the many nuclear accidents that occurred throughout the Cold War, since such data remained classified and guarded by the KGB. Without the use of radiation maps and measurements, they were trained to determine medicine doses by closely studying the affected human body and examining the nervous system, the hormonal levels and the blood cells. The observation and monitoring of the patients on-site allowed them to discern the damage at even very low doses.12

From the very first days of the accident, we see that multiple methods of observing, quantifying and visualizing radioactivity have been developed, from the radiation maps that delineate Exclusion Zones controlling people’s movement through georeferencing of collected measurements, to onsite medical examinations of the exposed-to-radiation human bodies. Throughout the years, scientists and artists have strived to form media that can represent the experience of this peculiar geography.

The “Elephant’s Foot”, one of the most radioactive elements in Chernobyl, was photographed by Artur Kornayev, the Deputy Director of the New Confinement, in 1996.

Initially, a very significant experiential component of the territory is the constant reminder of the radiation through the sounds and rhythms of the Geiger counters and dosimeters. The estimated spillage of radioactive waste sums up to around fifty to two-hundred million curies from the blown Reactor Four13, which remains detectable through its irregular expansion and dispersal in the surrounding area. The photographer Gerd Ludwig, in sharing with us his visit to the Zone, argues that his measuring equipment was extremely valuable in his journey, since even the guides that accompanied him

were not aware that certain areas were highly radioactive and unsafe. As he claims, they did not realize that radiation can move around as the wind blows the surface soil around.14 In a separate visit, Nicola Shulman states that her tour guide provided them with dosimeters, warming them that they will be continuously going off within the Zone, which is exceeding the warning level of radiation to which they were calibrated. Nicola could feel her dosimeter vibrating and beeping crazily in her clothes during a walk through an abandoned village.15

Notice explaining the health impacts that various levels of radiation exposure have on the human body.

Original document in Russian (left) and translation in English (right).

Original document in Russian (left) and translation in English (right).

In these journeys, it is not only the sound but also the scenery of abandonment and decay that reveals the past catastrophe. After the evacuation, the Zone was left to decay, with the vegetation left to uncontrollably grow and take over the landscape. Daniel Bürkner suggests that the photographic attempts to represent the radioactive landscape often put forth an object that projects sociological and philosophical criticism, proposing a post-industrial nature taking over the established civilization. The Chernobyl disaster is depicted as nature’s act of revenge against the failed technological reality and human agency on the landscape. In the meantime, the “dichotomy between rural aesthetics and lethal contamination” reveals the massive environmental pollution, which is oftentimes projected as a “mythological transformation” of the land into an otherworldly strange new reality.16

Igor Kostin was one the first photographers of Chernobyl’s radioactive scenes, becoming a major figure in the documentation of the immediate aftermath of the accident. He was present on-site from the first day after the nuclear explosion and was one of the few that recorded the initial acts of decontamination and changes that significantly altered the appearance of the

Igor Kostin was one the first photographers of Chernobyl’s radioactive scenes, becoming a major figure in the documentation of the immediate aftermath of the accident. He was present on-site from the first day after the nuclear explosion and was one of the few that recorded the initial acts of decontamination and changes that significantly altered the appearance of the

surrounding landscape. His photographs were opposed to the official Soviet policy that desired a showcasing of the heroic, victorious decontaminating

workers in the field17, the efforts for the obliteration of the accident and the industry’s marketing strategies that commercialized through projects such as the “Miss Atom” beauty contest an environmental and humanistic tragedy.18 This might also explain why his works were not published in the USSR until after the first few years. His focus was not on the political agendas associated with the disaster, but rather on developing strategies to capture the invisible effects of the contamination through symbolic indicators. Images of natural scenery that seemed to be liberated from the human effect and freely flourishing in the landscape would often be accompanied by the symbol of radiation that was used as a reminder for the contaminated context of Chernobyl. The depicted sceneries and strategies of representation of the industrial element resemble Jürgen Nefzger’s photographs of the “Fluffy Clouds” that bring forth rural landscapes and activities with a background of nuclear power plants.19 Bürkner suggests that this “ironic edge to the natural plenitude” is important for the representation of the contamination, which is not profane in the viewing of the landscape itself.20

workers in the field17, the efforts for the obliteration of the accident and the industry’s marketing strategies that commercialized through projects such as the “Miss Atom” beauty contest an environmental and humanistic tragedy.18 This might also explain why his works were not published in the USSR until after the first few years. His focus was not on the political agendas associated with the disaster, but rather on developing strategies to capture the invisible effects of the contamination through symbolic indicators. Images of natural scenery that seemed to be liberated from the human effect and freely flourishing in the landscape would often be accompanied by the symbol of radiation that was used as a reminder for the contaminated context of Chernobyl. The depicted sceneries and strategies of representation of the industrial element resemble Jürgen Nefzger’s photographs of the “Fluffy Clouds” that bring forth rural landscapes and activities with a background of nuclear power plants.19 Bürkner suggests that this “ironic edge to the natural plenitude” is important for the representation of the contamination, which is not profane in the viewing of the landscape itself.20

Liquidators measure radiation levels within the 30 km Chernobyl Exclusion Zone. They use antiquated radiation counters, wear anti-chemical warfare suits that are unsuitable for protection against radioactivity and cover their faces with “pig muzzle” masks. Photographed by Igor Kostin in May 1986.

A doctor examines the patient in a sterile room at Moscow’s No. 6 Clinic. The examination is carried out in an individual, air-conditioned chamber via specially created openings to avoid direct contact and contamination. Photographed by Igor Kostin.

A doctor examines the patient in a sterile room at Moscow’s No. 6 Clinic. The examination is carried out in an individual, air-conditioned chamber via specially created openings to avoid direct contact and contamination. Photographed by Igor Kostin.

The photographic visualizations of the radioactive zones are in accordance to the textual descriptions of the in-person experiences of Chernobyl’s landscape. Nicola describes what she saw in her visit as an anarchic reality that is dominated by an “unhusbanded nature”. In her words:

“The grimness of a distant catastrophe can be hard to recollect when all around you the late-sleeping Ukrainian spring has finally jumped out of bed and is doing cartwheels around your head. Skeins of little birds weave patters in the sky. Birdsong rings from all directions. Wild roses burst out through stone, tree trunks absorb iron fences. It was hard to know if what we were looking at was hope or despair. What was certain is that this is a very unusual tourist site, having no curator to impose the ‘official version’, ‘nothing can be touched’—it is all radioactive—” 21

Such a viewpoint was also shared by Robert Polidori in his book of photographic collections “Pripyat and Chernobyl—Zones of Exclusion”. The portrayed remnants of interior spaces are accompanied by an image of nature that is flourishing, suggesting that it has become a victorious and superior agent within the decayed and abandoned civilization”.22 The excluded area is

represented as a symbol of a historic reversal, in which we are moving from the

“The grimness of a distant catastrophe can be hard to recollect when all around you the late-sleeping Ukrainian spring has finally jumped out of bed and is doing cartwheels around your head. Skeins of little birds weave patters in the sky. Birdsong rings from all directions. Wild roses burst out through stone, tree trunks absorb iron fences. It was hard to know if what we were looking at was hope or despair. What was certain is that this is a very unusual tourist site, having no curator to impose the ‘official version’, ‘nothing can be touched’—it is all radioactive—” 21

Such a viewpoint was also shared by Robert Polidori in his book of photographic collections “Pripyat and Chernobyl—Zones of Exclusion”. The portrayed remnants of interior spaces are accompanied by an image of nature that is flourishing, suggesting that it has become a victorious and superior agent within the decayed and abandoned civilization”.22 The excluded area is

represented as a symbol of a historic reversal, in which we are moving from the

industrial and technological reality back to the agrarian society of close

connection and dialogue with nature. Bürkner suggests that this sort of interpretation is, in fact, a paradox, since the depicted surface of nature is

hiding the reality of heavily contaminated soil, vegetables and fruit.23 One of the dangerous characteristics of radioactivity is perhaps this inability to quantify it to understand its scale and proportion from the visual perception and photographic representation. This property became the main concept for the photographic project “Atomgrad (Nature Abhors a Vacuum)” by artists Jane and Louise Wilson. The collection of large-format images of abandoned sites throughout Chernobyl and Pripyat as a result of their field trip to Ukraine in 2010 is capturing our inability to measure radioactivity in space. In each photograph, a large black-and-white ruler is positioned in reference to the various architectural elements of the captured interior spaces. The introduction of an investigative object resembles forensic photography in its attempt to document and measure the dimensions and properties of space, which we now see as an illusion since radiation surpasses the physical domain of our perception.24 In this realm of photography, there is no visualization of radioactivity, but rather an awareness or recognition for a hidden reality that exists beyond our senses.

connection and dialogue with nature. Bürkner suggests that this sort of interpretation is, in fact, a paradox, since the depicted surface of nature is

hiding the reality of heavily contaminated soil, vegetables and fruit.23 One of the dangerous characteristics of radioactivity is perhaps this inability to quantify it to understand its scale and proportion from the visual perception and photographic representation. This property became the main concept for the photographic project “Atomgrad (Nature Abhors a Vacuum)” by artists Jane and Louise Wilson. The collection of large-format images of abandoned sites throughout Chernobyl and Pripyat as a result of their field trip to Ukraine in 2010 is capturing our inability to measure radioactivity in space. In each photograph, a large black-and-white ruler is positioned in reference to the various architectural elements of the captured interior spaces. The introduction of an investigative object resembles forensic photography in its attempt to document and measure the dimensions and properties of space, which we now see as an illusion since radiation surpasses the physical domain of our perception.24 In this realm of photography, there is no visualization of radioactivity, but rather an awareness or recognition for a hidden reality that exists beyond our senses.

“Atomograd I: Nature Abhors a Vacuum” by artists Jane and Louise Wilson.

“Atomograd IV: Nature Abhors a Vacuum” by artists Jane and Louise Wilson.

We lack the ability to directly see the radioactive fallout in the Chernobyl zone, but we can experience and observe its ramifications through biological indicators on humans and other living beings. From the first years after the explosion, USSR reports include 299 hospitalized adults, including 137 of them with radiation sickness. In the Kyiv archives, Kate Brown states that she counted at least 40,000 cases of hospitalized people. In Belarus specifically from the 11,500 cases checked into the hospital, half of them were children, including many that were diagnosed with radiation sickness. Many of them were detected with radioactive iodine measured in a range of 30 to 1,500 rads. In the summer of 1986, there were multiple cases of lethargic children that were reported to have enlarged thyroids, suffering from anemia and presenting infections and various neurological tics.25 Brown shares her conversations with a local medical researcher, Liubiv Yevtushov, who pointed at her charts that revealed increasing birth defects, higher from three to six times in rates than in any other European average. She describes children that she met in surrounding villages that presented the effects of radioactivity through the physical twisting and spiraling limbs in their bodies.26 In her field trip to Chernihiv in northern Ukraine, Brown spoke with the women workers of a wool factory that was particularly contaminated. Radiation appeared to

them through biological indicators, and particularly when they witnessed bleeding from one of their co-worker’s mouth. This was followed by other reports of nose bleeds, dizziness and loss of consciousness. One day, one of them checked into the hospital completely anemic, requiring blood transfusions. The doses that were measured in two hundred of them were comparable to the ones detected in the “liquidators”, who were the personnel that dealt with the damages in the nuclear plant during the first days of the explosion. The wool factory workers were very much aware of the radioactive contamination of the municipal reservoir that was connected to the city pipes and they knew the victims of leukemia after the explosion. They were even aware of how radioactivity felt in their own bodies, demonstrating the parts that ached the most and comparing that to their extensive knowledge on how Caesium-137 would appear in the flesh, whereas Plutonium-239 and Ruthenium-106 would most likely aggregate in the bone marrow and the joints.27 These women did not need any sort of cartographic imagery or scientific device to visualize and quantify radiation. In fact, it was already present in their bodies, freely revealing itself through physical symptoms and feelings.

The New Safe Confinement in Chernobyl, shown under construction in 2013. The $2 billion structure is designed to replace the previous “Sarcophagus” and contain radioactive waste for the next 100 years. Photographed by Gerd Ludwig.

From a bodily sensation of radiation, we are now moving again outside and into the visual spectrum to discuss the series of biological indicators that appeared similarly in other living beings that remain in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone. There are multiple scientific methods that have been developed for the observation and representation of radioactivity in living beings, and the artist Cornelia Hesse-Honegger has followed one of the most systematic ones. Throughout her fieldwork and collection of insects, she methodically drew their patterns of evolution around power plants. Following a “truth to nature” paradigm and the development of a taxonomist analysis on the insects allows for clear visualization of the long-term impact of high radioactive levels on populations.28 Brown also narrates her unique experience of the vegetation in the Zone and her journey north of Kyiv at the town of O’Ishany along with the forester Ivan Gusin. There, she witnessed a peculiar pine tree of about 50 years old, which was growing in a disorganized fashion with curling branches and chaotic needles. Located in the center of a bomb crater, it was significantly mutated by the present radioactive energy that was apparently there from an earlier bomb test prior to the Chernobyl disaster. According to the biologists Mousseau and Møller, who have been conducting fieldwork in the Zone for years, supported that few pine trees would end up growing in places with higher than 40 microsieverts radioactivity, and in that case they would usually show marks of mutation. In the particular area of the Red Forest, which happened to receive much of the radioactive fallout from the Chernobyl explosion, its ground remained predominantly brown and

covered with undecomposed pine needles and thick layers of fallen leaves. In her description of the Red Forest, Brown mentions that the smell of these

covered with undecomposed pine needles and thick layers of fallen leaves. In her description of the Red Forest, Brown mentions that the smell of these

places was mostly one of decomposition rather than the flourishing of

vegetation. The biological indicators, in this case, were in complete accordance to her dosimeter measurements of around 30-35 and leading up to 42 microsieverts per hour. What was surprising, though, was that when she returned back to the road, the radioactive measurement dropped in half. The forest was indeed more radioactive than the artificial asphalt structure of the road, and the scientific explanation for that was that the biological organisms tended to concentrate more radioactive isotopes, making the radiation reading in environments of higher populations of living organisms higher.29

In her communication with the biologists Mousseau and Møller, Brown recognizes that for their research, they treat the Chernobyl Zone as a living laboratory. By being present in the field, they have the benefit of the immediacy of the landscape that presents irregular and disorderly concentrations of radioactive material. Through the behavior of the forest and the land and the visible impact of radioactivity in biological systems, they are able to identify territories even outside of the Zone—and where people are permitted to live and farm— which is more radioactive than the excluded and evacuated regions.30 Brown characterizes their work as a “kind of science left to more-than-human landscapes, a science that is dirty, painful and hazardous as much as it is creating and invigorating”. Their “living laboratory” is a collection of remnants of “spent ammunition, heavy metals, chemical toxins and radioactive waste distribute at a frenetic pace”, which becomes visible on the form and growth of the local plant life and the larger context of the ecosystem.31

vegetation. The biological indicators, in this case, were in complete accordance to her dosimeter measurements of around 30-35 and leading up to 42 microsieverts per hour. What was surprising, though, was that when she returned back to the road, the radioactive measurement dropped in half. The forest was indeed more radioactive than the artificial asphalt structure of the road, and the scientific explanation for that was that the biological organisms tended to concentrate more radioactive isotopes, making the radiation reading in environments of higher populations of living organisms higher.29

In her communication with the biologists Mousseau and Møller, Brown recognizes that for their research, they treat the Chernobyl Zone as a living laboratory. By being present in the field, they have the benefit of the immediacy of the landscape that presents irregular and disorderly concentrations of radioactive material. Through the behavior of the forest and the land and the visible impact of radioactivity in biological systems, they are able to identify territories even outside of the Zone—and where people are permitted to live and farm— which is more radioactive than the excluded and evacuated regions.30 Brown characterizes their work as a “kind of science left to more-than-human landscapes, a science that is dirty, painful and hazardous as much as it is creating and invigorating”. Their “living laboratory” is a collection of remnants of “spent ammunition, heavy metals, chemical toxins and radioactive waste distribute at a frenetic pace”, which becomes visible on the form and growth of the local plant life and the larger context of the ecosystem.31

Pine trees in Al’many Swamp growing from a bomb crater (top) and shrub-like pine trees along with bare ground in the Red Forest (bottom). Photographed by Kate Brown.

Apart from the portion of the radioactive reality that can be perceived through our visual sense, it is also quite interesting to delve into the work of artists and photographers that experimented in their forms of capturing devices and media to unravel the invisibility of radiation itself. In referring back to Bürkner, there seem to be two distinct ways in which photography was used in representing Chernobyl’s landscape, which he defines as the iconographic projection—or the representation of landscape through a symbolic meaning—and the material projection, which involves the use of photography’s capacity to photochemically reveal hidden realities.32 This second case of projection, which we will currently focus on, is a rejection of any traditional or conventional forms of visual representation. The artist Gustav Metzger on the visualization of radioactivity stated that the only method that would completely allow the reflection of nuclear contexts would be the actual physical destruction of the medium that is utilized by radiation itself. By such a method, radioactivity presents itself in the form of exposure, rendering an image that has a grainy and blurred quality. By employing an

epistemic quality of photography, the Brazilian artist Alice Miceli has extensively worked on capturing radioactivity through the use of photochemical material. By attaching large-scale x-ray negatives to trees and houses in the Chernobyl Zone, she was able to retrieve long exposure shots of radioactive emissions. The results of her visual investigations were presented at the Transmediale 2010 in Berlin, placed in backlit lightboxes that showed the images’ abstract and fluid radiation figures. These low-dose radioactivity exposures on the photographic x-ray negatives form abstract representations of the landscape, in comparison to the typical iconographic projections. Although intriguing, Bürkner is concerned with the reliability of these images to accurately represent radioactivity, arguing that the final forms could potentially just be random chemical occurrences. Nevertheless, the medium of the photographic representation of radioactive landscapes is capable of bringing to light invisible forces that escape and transgress our visual spectrum.33

fragment of a field III - 9.120 μSv

[07.05.09 - 21.07.09]

[07.05.09 - 21.07.09]

fragment of a window I - 2.494 μSv

[21.01.09 - 07.04.09]

[21.01.09 - 07.04.09]

fragment of a field V - 9.120 μSv

[07.05.09 - 21.07.09]

[07.05.09 - 21.07.09]

fragment of the trunk of a tree II - 7.356 μSv

[07.05.09 - 21.07.09]

fragment of a field II - 9.120 μSv

[07.05.09 - 21.07.09]

![]()

[07.05.09 - 21.07.09]

fragment of a wooden wall IV - 2.956 μSv

[21.01.09 - 07.04.09]

[21.01.09 - 07.04.09]

Chernobyl Project: a series of radiographs produced by artist Alice Miceli in

Chernobyl’s Nuclear Exclusion Zone during 2006-2010.

Chernobyl’s Nuclear Exclusion Zone during 2006-2010.

In examining the capacities of the photographic lens to capture parts of the reality that remain invisible to the naked eye, let’s now focus our attention on one of the earliest artistic documentation of the Chernobyl accident, through the Ukrainian filmmaker Vladimir Shevchenko and his “Chernobyl: Chronicle of Difficult Weeks.” Three days after the accident in the Reactor Four in the Chernobyl Nuclear Plant on April 26th, Shevchenko was granted permission to enter the site and fly over to document the decontamination work of the liquidators. After the first recordings of the scene, the filmmaker was disturbed and surprised by the incandescent marks that would randomly appear in his film.34 Upon further investigation and examination of the developed footage, he realized it wasn’t his film that was defective. In fact, he came to the conclusion that the strange image and sound that mysteriously appeared was radioactivity itself, exposed in the form of decaying particles moving through the casing of the camera, rearranging the molecules of his film. Susan Schuppli describes the tiny flares that rapidly ignite the film’s surface as “sparking and crackling”, conjuring “a pyrotechnics of syncopated spectrality.” Particularly in the first scenes and the fly over the site of the exploded Reactor Four, the interplay of the distorted image and sound resemble the Geiger counters and dosimeters with their warnings and alarms. The visual representation of the landscape is superimposed by the interference of radiation, with the viewers becoming witnesses of the

otherwise invisible forces and movements of radioactivity through space. According to Schuppli, this audiovisual disruption “collapses the distinction between representation and the real, forcing a rethinking of the ontological nature of media matter as merely a fixed record of events that provides evidence of a moment captured in time”.35

Years later after the production of the “Chernobyl: Chronicle of Difficult Weeks”, the artists Jane and Louise Wilson met with various surviving members of the film’s crew, who informed them that the camera used for the shooting was so contaminated and radioactive that it was ultimately disposed of somewhere underground. The radiation that distorted the film with audiovisual effects remained in the physical object of the medium, compromising its afterlife and altering its identity to now become a lethal weapon that would need to be immediately removed.36 Throughout the process of recording and filming, Chernobyl’s radiation did not only possess the film and the physical medium of the camera, but unfortunately the filmmaker himself. On March 29th 1987, Vladimir Shevchenko passed away from extensive exposure to radiation.37

Years later after the production of the “Chernobyl: Chronicle of Difficult Weeks”, the artists Jane and Louise Wilson met with various surviving members of the film’s crew, who informed them that the camera used for the shooting was so contaminated and radioactive that it was ultimately disposed of somewhere underground. The radiation that distorted the film with audiovisual effects remained in the physical object of the medium, compromising its afterlife and altering its identity to now become a lethal weapon that would need to be immediately removed.36 Throughout the process of recording and filming, Chernobyl’s radiation did not only possess the film and the physical medium of the camera, but unfortunately the filmmaker himself. On March 29th 1987, Vladimir Shevchenko passed away from extensive exposure to radiation.37

Clips from Volodymyr Shevchenko’s “Chernobyl - Chronicle of Difficult Weeks”, produced in 1986.

The Ukrainian filmmaker documents the first months after the nuclear accident.

The Ukrainian filmmaker documents the first months after the nuclear accident.

Within the last thirty-four years after Chernobyl’s explosion, there have been various methods that have been developed to visualize and perceive the resultant radioactive territory. The initial attempts from the part of the authorities included using the dosimeters in various areas of the surrounding region and cartographically represent the anomalous dispersal of fallout material in the interior and exterior USSR. The assumed thresholds of risk and safety of radiation for the human bodies became the base for the delineation of the legal borders of the Exclusion Zone, a territory evacuated from all people. Throughout the years, photographic projects have attempted to capture the complex relationship between the “flourishing” vegetation and wildlife and the radioactive remnants that will haunt the region for thousands of years. In this paradoxical reality captured in photography, radioactivity remains an invisible force, but with significant physical ramifications. Various biological indicators in humans and other living beings show its resultant distortions and mutations. From the visual presentation of the impact on the exterior skin of the victim, we are moving to the literal embodiment of radioactivity through the wool factory workers’ aches, the children’s enlarged thyroids and the radiation sickness, as well as also the irregular growth of pine trees and decomposition and decay of the Red Forest. From the visible impact of radioactivity on the landscape, photography

was also used more experimentally to expose some of the hidden layers through various

photochemical techniques, such as Alice Miceli’s x-ray photographs of various artifacts in the Zone. The accidental appearance of radiation in Shevshenko’s film provides a visualization not only of the environmental conditions of the Reactor Four, but also of the radiation absorbed by the medium itself and, ultimately, even the lethal radioactive dosage for the filmmaker’s body.

In the examination of all the various methods of visualization and interpretation of the radioactive landscape of Chernobyl, there is no single medium that can successfully capture the full extent of the current condition. Through the composition of textual stories and audiovisual elements, we are closer to the perception and conception of the complexity and invisibility of the radioactive landscape. In the emergence of the geologic epoch of the Anthropocene, our actions are agents of the planet will be followed by unpredictability, uncertainty and invisibility. Along with our technological and scientific evolution, it is essential to develop means of representing such phenomena along with their resultant byproduct emerging landscapes.

photochemical techniques, such as Alice Miceli’s x-ray photographs of various artifacts in the Zone. The accidental appearance of radiation in Shevshenko’s film provides a visualization not only of the environmental conditions of the Reactor Four, but also of the radiation absorbed by the medium itself and, ultimately, even the lethal radioactive dosage for the filmmaker’s body.

In the examination of all the various methods of visualization and interpretation of the radioactive landscape of Chernobyl, there is no single medium that can successfully capture the full extent of the current condition. Through the composition of textual stories and audiovisual elements, we are closer to the perception and conception of the complexity and invisibility of the radioactive landscape. In the emergence of the geologic epoch of the Anthropocene, our actions are agents of the planet will be followed by unpredictability, uncertainty and invisibility. Along with our technological and scientific evolution, it is essential to develop means of representing such phenomena along with their resultant byproduct emerging landscapes.

REFERENCES

1 Pravin P. Parekh et al., “Radioactivity in Trinitite Six Decades Later,” Journal of Environmental Radioactivity 85, no. 1 (January 2006): 103–120, 104.

2 Gerd Ludwig and Meg Ryan Heery, “Ripple Effect,” American Photomag, May-June 2014, 33.

3 Gabrielle Decamous, “Nuclear Activities and Modern Catastrophes: Art Faces the Radioactive Waves,” Leonardo 44, no. 2 (2011): 124–132, 130.

4 Daniel Bürkner, “The Chernobyl Landscape and the Aesthetics of Invisibility,” Photography and Culture 7, no. 1 (March 2014): 21–39, 21.

5 Gabrielle Decamous, 128.

6 Daniel Bürkner, 22.

7 Kate Brown, “Marie Curie’s Fingerprint: Nuclear Spelunking in the Chernobyl Zone,” in Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet: Ghosts and Monsters of the Anthropocene, by Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing et al. (University of Minnesota Press, 2017), G33.

8 Philip R. Pryde, Environmental Management in the Soviet Union (Cambridge [Eng.] ; New York : Cambridge University Press, 1991), 45.

9 Richard North, “Living with Catastrophe,” Independent, December 10, 1995, https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/living-with-catastrophe-1524915.html.

10 “Forsmark: How Sweden Alerted the World about the Danger of Chernobyl Disaster,” European Parliament, May 15, 2014, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/headlines/society/20140514STO47018/forsmark-how-sweden-alerted-the-world-about-the-danger-of-chernobyl-disaster.

11 Nicola Shulman, “Nuclear Holiday,” New Criterion 38, no. 1 (2019): 18–22, 20.

12 Kate Brown, “Learning to Read the Great Chernobyl Acceleration: Literacy in the More-than-Human Landscapes,” Current Anthropology 60, no. S20 (August 1, 2019): S198–208, S199.

13 Kate Brown, “Learning to Read the Great Chernobyl Acceleration: Literacy in the More-than-Human Landscapes,” S198.

14 Gerd Ludwig and Meg Ryan Heery, “Ripple Effect,” American Photomag, June 2014, 30.

15 Nicola Shulman, 19.

16 Daniel Bürkner, 22-23.

17 Daniel Bürkner, 24.

18 Gabrielle Decamous, 130.

19 Daniel Bürkner, 26.

20 Daniel Bürkner, 24.

21 Nicola Shulman, 20.

22 Daniel Bürkner, 29.

23 Daniel Bürkner, 30.

24 Susan Schuppli, “Material Malfeasance: Trace Evidence of Violence in Three Image-Acts,” Photoworks, no. 17 (2011): 28–33, 30.

25 Kate Brown, “Learning to Read the Great Chernobyl Acceleration: Literacy in the More-than-Human Landscapes,” S198.

26 Kate Brown, “Learning to Read the Great Chernobyl Acceleration: Literacy in the More-than-Human Landscapes,” S200.

27 Kate Brown, “Learning to Read the Great Chernobyl Acceleration: Literacy in the More-than-Human Landscapes,” S199.

28 Gabrielle Decamous, 130.

29 Kate Brown, “Learning to Read the Great Chernobyl Acceleration: Literacy in the More-than-Human Landscapes,” S207.

30 Kate Brown, “Learning to Read the Great Chernobyl Acceleration: Literacy in the More-than-Human Landscapes,” S205.

31 Kate Brown, “Learning to Read the Great Chernobyl Acceleration: Literacy in the More-than-Human Landscapes,” S208.

32 Daniel Bürkner, 22.

33 Daniel Bürkner, 35.

34 Susan Schuppli, 28.

35 Susan Schuppli, 30.

36 Susan Schuppli, 30.

37 Reuters, “A Soviet Film Maker at Chernobyl in ’86 Is Dead of Radiation,” The New York Times, May 30, 1987, sec. World.

2 Gerd Ludwig and Meg Ryan Heery, “Ripple Effect,” American Photomag, May-June 2014, 33.

3 Gabrielle Decamous, “Nuclear Activities and Modern Catastrophes: Art Faces the Radioactive Waves,” Leonardo 44, no. 2 (2011): 124–132, 130.

4 Daniel Bürkner, “The Chernobyl Landscape and the Aesthetics of Invisibility,” Photography and Culture 7, no. 1 (March 2014): 21–39, 21.

5 Gabrielle Decamous, 128.

6 Daniel Bürkner, 22.

7 Kate Brown, “Marie Curie’s Fingerprint: Nuclear Spelunking in the Chernobyl Zone,” in Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet: Ghosts and Monsters of the Anthropocene, by Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing et al. (University of Minnesota Press, 2017), G33.

8 Philip R. Pryde, Environmental Management in the Soviet Union (Cambridge [Eng.] ; New York : Cambridge University Press, 1991), 45.

9 Richard North, “Living with Catastrophe,” Independent, December 10, 1995, https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/living-with-catastrophe-1524915.html.

10 “Forsmark: How Sweden Alerted the World about the Danger of Chernobyl Disaster,” European Parliament, May 15, 2014, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/headlines/society/20140514STO47018/forsmark-how-sweden-alerted-the-world-about-the-danger-of-chernobyl-disaster.

11 Nicola Shulman, “Nuclear Holiday,” New Criterion 38, no. 1 (2019): 18–22, 20.

12 Kate Brown, “Learning to Read the Great Chernobyl Acceleration: Literacy in the More-than-Human Landscapes,” Current Anthropology 60, no. S20 (August 1, 2019): S198–208, S199.

13 Kate Brown, “Learning to Read the Great Chernobyl Acceleration: Literacy in the More-than-Human Landscapes,” S198.

14 Gerd Ludwig and Meg Ryan Heery, “Ripple Effect,” American Photomag, June 2014, 30.

15 Nicola Shulman, 19.

16 Daniel Bürkner, 22-23.

17 Daniel Bürkner, 24.

18 Gabrielle Decamous, 130.

19 Daniel Bürkner, 26.

20 Daniel Bürkner, 24.

21 Nicola Shulman, 20.

22 Daniel Bürkner, 29.

23 Daniel Bürkner, 30.

24 Susan Schuppli, “Material Malfeasance: Trace Evidence of Violence in Three Image-Acts,” Photoworks, no. 17 (2011): 28–33, 30.

25 Kate Brown, “Learning to Read the Great Chernobyl Acceleration: Literacy in the More-than-Human Landscapes,” S198.

26 Kate Brown, “Learning to Read the Great Chernobyl Acceleration: Literacy in the More-than-Human Landscapes,” S200.

27 Kate Brown, “Learning to Read the Great Chernobyl Acceleration: Literacy in the More-than-Human Landscapes,” S199.

28 Gabrielle Decamous, 130.

29 Kate Brown, “Learning to Read the Great Chernobyl Acceleration: Literacy in the More-than-Human Landscapes,” S207.

30 Kate Brown, “Learning to Read the Great Chernobyl Acceleration: Literacy in the More-than-Human Landscapes,” S205.

31 Kate Brown, “Learning to Read the Great Chernobyl Acceleration: Literacy in the More-than-Human Landscapes,” S208.

32 Daniel Bürkner, 22.

33 Daniel Bürkner, 35.

34 Susan Schuppli, 28.

35 Susan Schuppli, 30.

36 Susan Schuppli, 30.

37 Reuters, “A Soviet Film Maker at Chernobyl in ’86 Is Dead of Radiation,” The New York Times, May 30, 1987, sec. World.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Barad, Karen. “No Small Matter: Mushroom Clouds, Ecologies of Nothingness, and Strange Topologies of Spacetimemattering.” In Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet: Ghosts and Monsters of the Anthropocene, by Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, Nils Bubandt, Elaine Gan, and Heather Anne Swanson. University of Minnesota Press, 2017.

Blackford, James. “Red Skies: Soviet Science Fiction.” Sight and Sound 21, no. 7 (2011): 45–48.

Brown, Kate. “Learning to Read the Great Chernobyl Acceleration: Literacy in the More-than-Human Landscapes.” Current Anthropology 60, no. S20 (August 1, 2019): S198–208.

———. “Marie Curie’s Fingerprint: Nuclear Spelunking in the Chernobyl Zone.” In Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet: Ghosts and Monsters of the Anthropocene, by Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, Nils Bubandt, Elaine Gan, and Heather Anne Swanson. University of Minnesota Press, 2017.

———. Plutopia: Nuclear Families, Atomic Cities, and the Great Soviet and American Plutonium Disasters. Cary, UNITED STATES: Oxford University Press, Incorporated, 2013.

Bürkner, Daniel. “The Chernobyl Landscape and the Aesthetics of Invisibility.” Photography and Culture 7, no. 1 (March 2014): 21–39.

Decamous, Gabrielle. “Nuclear Activities and Modern Catastrophes: Art Faces the Radioactive Waves.” Leonardo 44, no. 2 (2011): 124–132.

European Parliament. “Forsmark: How Sweden Alerted the World about the Danger of Chernobyl Disaster,” May 15, 2014. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/headlines/society/20140514STO47018/forsmark-how-sweden-alerted-the-world-about-the-danger-of-chernobyl-disaster.

Glikson, Andrew Yoram. The Plutocene: Blueprints for a Post-Anthropocene Greenhouse Earth. 1st ed. 2017. Modern Approaches in Solid Earth Sciences, 13. Cham: Springer International Publishing : Imprint: Springer, 2017.

Ludwig, Gerg, and Meg Ryan Heery. “Ripple Effect.” American Photomag, June 2014.

North, Richard. “Living with Catastrophe.” Independent, December 10, 1995. https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/living-with-catastrophe-1524915.html.

Parekh, Pravin P., Thomas M. Semkow, Miguel A. Torres, Douglas K. Haines, Joseph M. Cooper, Peter M. Rosenberg, and Michael E. Kitto. “Radioactivity in Trinitite Six Decades Later.” Journal of Environmental Radioactivity 85, no. 1 (January 2006): 103–20.

Pryde, Philip R. Environmental Management in the Soviet Union. Cambridge [Eng.] ; New York : Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Reuters. “A Soviet Film Maker at Chernobyl in ’86 Is Dead of Radiation.” The New York Times, May 30, 1987, sec. World. https://www.nytimes.com/1987/05/30/world/a-soviet-film-maker-at-chernobyl-in-86-is-dead-of-radiation.html. Schuppli, Susan. “Material Malfeasance: Trace Evidence of Violence in Three Image-Acts.” Photoworks, no. 17 (2011): 28–33.

Shulman, Nicola. “Nuclear Holiday.” New Criterion 38, no. 1 (2019): 18–22.

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt, Nils Bubandt, Elaine Gan, and Heather Anne Swanson. Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet: Ghosts and Monsters of the Anthropocene. University of Minnesota Press, 2017.

Blackford, James. “Red Skies: Soviet Science Fiction.” Sight and Sound 21, no. 7 (2011): 45–48.

Brown, Kate. “Learning to Read the Great Chernobyl Acceleration: Literacy in the More-than-Human Landscapes.” Current Anthropology 60, no. S20 (August 1, 2019): S198–208.

———. “Marie Curie’s Fingerprint: Nuclear Spelunking in the Chernobyl Zone.” In Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet: Ghosts and Monsters of the Anthropocene, by Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, Nils Bubandt, Elaine Gan, and Heather Anne Swanson. University of Minnesota Press, 2017.

———. Plutopia: Nuclear Families, Atomic Cities, and the Great Soviet and American Plutonium Disasters. Cary, UNITED STATES: Oxford University Press, Incorporated, 2013.

Bürkner, Daniel. “The Chernobyl Landscape and the Aesthetics of Invisibility.” Photography and Culture 7, no. 1 (March 2014): 21–39.

Decamous, Gabrielle. “Nuclear Activities and Modern Catastrophes: Art Faces the Radioactive Waves.” Leonardo 44, no. 2 (2011): 124–132.

European Parliament. “Forsmark: How Sweden Alerted the World about the Danger of Chernobyl Disaster,” May 15, 2014. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/headlines/society/20140514STO47018/forsmark-how-sweden-alerted-the-world-about-the-danger-of-chernobyl-disaster.

Glikson, Andrew Yoram. The Plutocene: Blueprints for a Post-Anthropocene Greenhouse Earth. 1st ed. 2017. Modern Approaches in Solid Earth Sciences, 13. Cham: Springer International Publishing : Imprint: Springer, 2017.

Ludwig, Gerg, and Meg Ryan Heery. “Ripple Effect.” American Photomag, June 2014.

North, Richard. “Living with Catastrophe.” Independent, December 10, 1995. https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/living-with-catastrophe-1524915.html.

Parekh, Pravin P., Thomas M. Semkow, Miguel A. Torres, Douglas K. Haines, Joseph M. Cooper, Peter M. Rosenberg, and Michael E. Kitto. “Radioactivity in Trinitite Six Decades Later.” Journal of Environmental Radioactivity 85, no. 1 (January 2006): 103–20.

Pryde, Philip R. Environmental Management in the Soviet Union. Cambridge [Eng.] ; New York : Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Reuters. “A Soviet Film Maker at Chernobyl in ’86 Is Dead of Radiation.” The New York Times, May 30, 1987, sec. World. https://www.nytimes.com/1987/05/30/world/a-soviet-film-maker-at-chernobyl-in-86-is-dead-of-radiation.html. Schuppli, Susan. “Material Malfeasance: Trace Evidence of Violence in Three Image-Acts.” Photoworks, no. 17 (2011): 28–33.

Shulman, Nicola. “Nuclear Holiday.” New Criterion 38, no. 1 (2019): 18–22.

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt, Nils Bubandt, Elaine Gan, and Heather Anne Swanson. Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet: Ghosts and Monsters of the Anthropocene. University of Minnesota Press, 2017.